5.5 Ethernet

Ethernet has pretty much taken over the LAN market.

As recently as the 1980s and the early 1990s, Ethernet faced many challenges

from other LAN technologies, including token ring, FDDI and ATM. Some of

these other technologies succeeded at capturing a part of the market share

for a few years. But since its invention in the mid-1970, Ethernet has

continued to evolve and grow, and has held on to its dominant market share.

Today, Ethernet is by far the most prevalent LAN technology, and

is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. One might say

that Ethernet has been to local area networking what

the Internet has been to global networking:

There are many reasons for Ethernet's success.

First, Ethernet was the first widely-deployed high-speed LAN. Because it

was deployed early, network administrators became intimately familiar with

Ethernet -- its wonders and its quirks -- and were reluctant to switch

over to other LAN technologies when they came on the scene. Second, token

ring, FDDI and ATM are more complex and expensive than Ethernet, which

further discouraged network administrators from switching over. Third,

the most compelling reason to switch to another LAN technology (such as

FDDI or ATM) was usually the higher data rate of the new technology; however,

Ethernet always fought back, producing versions that operated at equal

data rates or higher. Switched Ethernet was also introduced in the early

1990s, which further increased its effective data rates. Finally, because

Ethernet has been so popular, Ethernet hardware (in particular, network

interface cards) has become a commodity and is remarkably cheap. This low

cost is also due o the fact that Ethernet's multiple access protocol, CSMA/CD,

is totally decentralized, which has also contributed to the low cost and

simple design.

The original Ethernet LAN, as shown in Figure 5.5-1, was invented in

the mid 1970s by Bob Metcalfe. An excellent source of online information

about Ethernet is Spurgeon's Ethernet Web Site [Spurgeon

1999].

Figure 5.5-1: The original Metcalfe design led to the 10Base5

Ethernet standard, which included an interface cable that connected the

Ethernet adapter (i.e., interface) to an external transceiver. Drawing

taken from Charles Spurgeon's Ethernet Web Site.

5.5.1 Ethernet Basics

Today Ethernet comes in many shapes and forms. An

Ethernet LAN can have a "bus topology" or a "star topology." An Ethernet

LAN can run over coaxial cable, twisted-pair copper wire, or fiber optics.

Furthermore, Ethernet can transmit data at different rates, specifically,

at 10 Mbps, 100 Mbps and 1 Gbps. But even though Ethernet comes in many

flavors, all of the Ethernet technologies share a few important characteristics.

Before examining the different technologies, let's first take a look at

the common characteristics.

Ethernet Frame Structure

Given that there are many different Ethernet technologies

on the market today, what do they have in common, what

binds them together with a common name? First and foremost is the Ethernet

frame structure. All of the Ethernet technologies -- whether they use coaxial

cable or copper wire, whether they run at 10 Mbps, 100 Mbps or 1 Gbps --

use

the same frame structure.

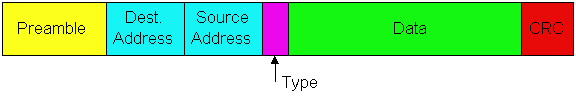

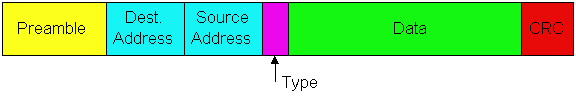

Figure 5.5-2: Ethernet frame structure

The Ethernet frame is shown in Figure 5.5-2. Once

we understand the Ethernet frame, we will already know a lot about Ethernet.

To put our discussion of the Ethernet frame in a tangible context, let

us consider sending an IP datagram from one host to another host, with

both hosts on the same Ethernet LAN. Let the sending adapter, adapter A,

have physical address AA-AA-AA-AA-AA-AA and the receiving adapter, adapter

B, have physical address BB-BB-BB-BB-BB-BB. The sending adapter encapsulates

the IP datagram within an Ethernet frame and passes the frame to the physical

layer. The receiving adapter receives the frame from the physical layer,

extracts the IP datagram, and passes the IP datagram to the network layer.

In this context, let us now examine the six fields

of the Ethernet frame:

-

Data Field (46 to 1500 bytes): This field

carries the IP datagram. The Maximum Transfer Unit (MTU) of Ethernet is

1500 bytes. This means that if the IP datagram exceeds 1500 bytes, then

the host has to fragment the datagram, as discussed in Section 4.4. The

minimum size of the data field is 46 bytes. This means that if the IP datagram

is less than 46 bytes, the data field has to be "stuffed" to fill

it out to 46 bytes. When stuffing is used, the data passed to the network

layer contains the stuffing as well as an IP datagram. The network layer

uses the length field in the IP datagram header to remove the stuffing.

-

Destination Address (6 bytes): This field

contains the LAN address of the destination adapter, namely, BB-BB-BB-BB-BB-BB.

When adapter B receives an Ethernet frame with destination address other

than its own physical address, BB-BB-BB-BB-BB-BB, or the LAN broadcast

address, it discards the frame. Otherwise, it passes the contents of the

data field to the network layer.

-

Source Address (6 bytes): This field contains

the LAN address of the adapter that transmits the frame onto the LAN, namely,

AA-AA-AA-AA-AA-AA.

-

Type Field (two bytes): The type field permits

Ethernet to "multiplex" network-layer protocols. To understand this idea,

we need to keep in mind that hosts can use other network-layer protocols

besides IP. In fact, a given host may support multiple network layer protocols,

and use different protocols for different applications. For this reason,

when the Ethernet frame arrives at adapter B, adapter B needs to know to

which network-layer protocol it should pass the contents of the data field.

IP and other data-link layer protocols (e.g., Novell IPX or AppleTalk)

each have there own, standardized type number. Furthermore, the ARP protocol

(discussed in the previous section) has its own type number. Note that

the type field is analogous to the protocol field in the network-layer

datagram and the port number fields in the transport-layer segment; all

of these fields serve to glue a protocol at one layer to a protocol at

the layer above.

-

Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC) (4 bytes): As

discussed in section 5.2, the purpose of the CRC field is to allow the

receiving adapter, adapter B, to detect whether any errors have been introduced

into the frame, i.e., if bits in the frame have been toggled. Causes of

bit errors include attenuation in signal strength and ambient electromagnetic

energy that leaks into the Ethernet cables and interface cards. Error detection

is performed as follows. When host A constructs the Ethernet frame, it

calculates a CRC field, which is obtained from a mapping of the other

bits in frame (except for the preamble bits). When host B receives the

frame, it applies the same mapping to the frame and checks to see if the

result of the mapping is equal to what is in the CRC field. This operation

at the receiving host is called the CRC check. If the CRC check

fails (that is, if the result of the mapping does not equal the contents

of the CRC field), then host B knows that there is an error in the frame.

-

Preamble: (8 bytes) The Ethernet frame

begins with an eight-byte preamble field. Each of the first seven bytes

of

the preamble is 10101010; the last byte is 10101011. The first seven bytes

of the preamble serve to "wake up" the receiving adapters and to synchronize

their clocks to that of the sender's clock. Why should the clocks be out

of synchronization? Keep in mind that adapter A aims

to transmit the frame at 10 Mbps, 100 Mbps or 1 Gbps, depending on the

type of Ethernet LAN. However, because nothing is absolutely perfect, adapter

A will not transmit the frame at exactly the target rate; there will

always be some drift from the target rate, a drift which is

not known a priori by the other adapters on the LAN. A receiving

adapter can lock onto adapter A's clock by simply locking onto the bits

in the first seven bytes of the preamble. The last two bits of the eighth

byte of the preamble (the first two consecutive 1s) alert adapter B that

the "important stuff" is about to come. When host B sees the

two consecutive 1s, it know that the next six bytes is the destination

address. An adapter can tell when a frame ends by simply detecting absence

of current.

An Unreliable Connectionless Service

All of the Ethernet technologies provide connectionless

service to the network layer. That is to say, when adapter A wants

to send a datagram to adapter B, adapter A encapsulates the datagram in

an Ethernet frame and sends the frame into the LAN, without first "handshaking"

with adapter B. This layer-2 connectionless service is analogous to IP's

layer-3 datagram service and UDP's layer-4 connectionless service.

All the Ethernet technologies provide an unreliable

service to the network layer. In particular when adapter B receives

a frame from A, adapter B does not send an acknowledgment when a frame

passes the CRC check (nor does it send a negative acknowledgment when a

frame fails the CRC check). Adapter A hasn't the slightest idea whether

a frame arrived correctly or incorrectly. When a frame fails the CRC check,

adapter B simply discards the frame. This lack of reliable transport (at

the link layer) helps to make Ethernet simple and cheap. But it also means

that the stream of datagrams passed to the network layer can have gaps.

If there are gaps due to discarded Ethernet frames,

does the application-layer protocol at host B see gaps as well? As we learned

in Chapter 3, this solely depends on whether the application is using UDP

or TCP. If the application is using UDP, then the application-layer protocol

in host B will indeed suffer from gaps in the data. On the other hand,

if the application is using TCP, then TCP in host B will not acknowledge

the discarded data, causing TCP in host A to retransmit. Note that

when TCP retransmits data, Ethernet retransmits the data as well. But we

should keep in mind that Ethernet doesn't know that it is retransmitting.

Ethernet thinks it is receiving a brand new datagram with brand new data,

even though this datagram contains data that has already been transmitted

at least once.

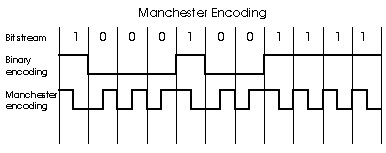

Baseband Transmission and Manchester Encoding

Ethernet uses baseband transmission, that is, the adapter sends a digital

signal directly into the broadcast channel. The interface card does not

shift the signal into another frequency band, as do ADSL and cable modem

systems. Ethernet also uses Manchester encoding, as shown in Figure 5.5-3.

With Manchester encoding each bit contains a transition; a 1 has a transition

from up to down, whereas a zero has a transition from down to up. The reason

for Manchester encoding is that the clocks in the sending and receiving

adapters are not perfectly synchronized. By including a transition in the

middle of each bit, the receiving host can synchronize its clock to that

of the sending host. Once the receiving adapter's clock is synchronized,

the receiver can delineate each bit and determine whether it is a one or

zero. Manchester encoding is a physical layer operation rather than a link-layer

operation; however, we have briefly described it here as it is used extensively

in Ethernet.

Figure 5.5-3: Manchester encoding

5.5.2 CSMA/CD: Ethernet's Multiple Access Protocol

Nodes in an Ethernet LAN are interconnected by a broadcast channel, so

that when an adapter transmits a frame, all the adapters on the LAN receive

the frame. As we discussed in section 5.3, Ethernet uses a CSMA/CD multiple

access algorithm. Summarizing our discussion from Section 5.3, recall that

CSMA/CD employs the following mechanisms:

-

An adapter may begin to transmit at any time, i.e., no slots are used.

-

An adapter never transmits a frame when it senses that some other adapter

is transmitting, i.e., it uses carrier-sensing.

-

A transmitting adapter aborts its transmission as soon as it detects that

another adapter is also transmitting, i.e., it uses collision detection.

-

Before attempting a retransmission, an adapter waits a random time that

is typically small compared to a frame time.

These mechanisms give CSMA/CD much better performance than slotted ALOHA

in a LAN environment. In fact, if the maximum propagation delay between

stations is very small, the efficiency of CSMA/CD can approach 100%. But

note that the second and third mechanisms listed above require each Ethernet

adapter to be able to (1) sense when some other adapter is transmitting,

and (2) detect a collision while it is transmitting. Ethernet adapters

perform these two tasks by measuring voltage levels before and during transmission.

Each adapter runs the CSMA/CD protocol without explicit coordination

with the other adapters on the Ethernet. Within a specific adapter, the

CSMA/CD protocol works as follows:

-

The adapter obtains a network-layer PDU from its parent node, prepares

an Ethernet frame, and puts the frame in an adapter buffer.

-

If the adapter senses that the channel is idle (i.e., there is no signal

energy from the channel entering the adapter), it starts to transmit the

frame. If the adapter senses that the channel is busy, it waits until it

senses no signal energy (plus a few hundred microseconds) and then starts

to transmit the frame.

-

While transmitting, the adapter monitors for the presence of signal energy

coming from other adapters. If the adapter transmits the entire frame without

detecting signal energy from other adapters, the adapter is done with the

frame.

-

If the adapter detects signal energy from other adapters while transmitting,

it stops transmitting its frame and instead transmits a 48-bit jam signal.

-

After aborting (i.e., transmitting the jam signal), the adapter enters

an exponential backoff phase. Specifically, when transmitting

a given frame, after experiencing the nth collision in a row

for this frame, the adapter chooses a value for K at random from

{0,1,2,...,2m - 1} where m:= min(n,10).

The adapter then waits K x 512 bit times and then returns to Step

2.

A few comments about the CSMA/CD protocol are certainly in order. The purpose

of the jam signal is to make sure that all other transmitting adapters

become aware of the collision. Let's look at an example. Suppose adapter

A begins to transmit a frame, and just before A's signal reaches adapter

B, adapter B begins to transmit. So B will have transmitted only a few

bits when it aborts its transmission. These few bits will indeed propagate

to A, but they may not constitute enough energy for A to detect the collision.

To make sure that A detects the collision (so that it to can also abort),

B transmits the 48-bit jam signal.

Next consider the exponential backoff algorithm. The first thing to

notice here is that a bit time (i.e., the time to transmit a single

bit) is very short; for a 10 Mbps Ethernet, a bit time is .1 microseconds.

Now let's look at an example. Suppose that an adapter attempts for the

first time to transmit a frame, and while transmitting it detects a collision.

The adapter then chooses K=0 with probability .5 and chooses K=1

with probability .5. If the adapter chooses K=0, then it immediately

jumps to Step 2 after transmitting the jam signal. If the adapter chooses

K=1,

it waits 51.2 microseconds before returning to Step 2. After a second collision,

K

is chosen with equal probability from {0,1,2,3}. After three collisions,

K

is chosen with equal probability from {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7}. After ten

or more collisions, K is chosen with equal probability from {0,1,2,...,1023}.

Thus the size of the sets from which K is chosen grows exponentially

with the number of collisions (until n=10); it is for this reason

that Ethernet's backoff algorithm is referred to as "exponential backoff".

The Ethernet standard imposes limits on the distance between any two

nodes. These limits ensure that if adapter A chooses a lower value of K

than all the other adapters involved in a collision, then adapter A will

be able to transmit its frame without experiencing a new collision. We

will explore this property in more detail in the homework problems.

Why use exponential backoff? Why not, for example, select K from

{0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7} after every collision? The reason is that when an adapter

experiences its first collision, it has no idea how many adapters are involved

in the collision. If there are only a small number of colliding adapters,

it makes sense to choose K from a small set of small values.

On the other hand, if many adapters are involved in the collision, it makes

sense to choose K from a larger, more dispersed set of values (why?).

By increasing the size of the set after each collision, the adapter appropriately

adapts to these different scenarios.

We also note here that each time an adapter prepares a new frame for

transmission, it runs the CSMA/CD algorithm presented above. In particular,

the adapter does not take into account any collisions that may have occurred

in the recent past. So it is possible that an adapter with a new frame

will be able to immediately sneak in a successful transmission while

several other adapters are in the exponential backoff state.

Ethernet Efficiency

When only one node has a frame to send (which is typically the case), the

node can transmit at the full rate of the Ethernet technology (either 10

Mbps, 100 Mbps, or 1 Gbps). However, if many nodes have frames to transmit,

the effective transmission rate of the channel can be much less. We define

the efficiency of Ethernet to be the long-run fraction of time during

which frames are being transmitted on the channel without collisions when

there is a large number of active nodes, with each node having a large

number of frames to send. In order to present a closed-form approximation

of the efficiency of Ethernet, let tprop denote the maximum

time it takes signal energy to propagate between any two adapters. Let

ttrans be the time to transmit a maximum size Ethernet frame

(approximately 1.2 msecs for a 10 Mbps Ethernet). A derivation of the efficiency

of Ethernet is beyond the scope of this book (see [Lam

1980] and [Bertsekas 1992]). Here we simply

state the following approximation:

efficiency = 1/(1+ 5 tprop/ttrans).

We see from this formula that as tprop approaches 0,

the efficiency approaches 1. This is intuitive because if the propagation

delay is zero, colliding nodes will abort immediately without wasting the

channel. Also, as ttrans becomes very large, efficiency approaches

1. This is also intuitive because when a frame grabs the channel, it will

hold on to the channel for a very long time; thus the channel will

be doing productive work most of the time.

5.5.3 Ethernet Technologies

The most common Ethernet technologies today are 10Base2,

which uses thin coaxial cable in a bus topology and has a transmission

rate of 10 Mbps; 10BaseT, which uses twisted-pair cooper wire in a star

topology and has a transmission rate of 10 Mbps; 100BaseT, which typically

uses twisted-pair cooper wire in a star topology and has a transmission

rate of 100 Mbps; and Gigabit Ethernet, which uses both fiber and twisted-pair

cooper wire and transmits at a rate of 1 Gbps. These Ethernet technologies

are standardized by the IEEE 802.3 working groups. For this reason, Ethernet

is often referred to as an 802.3 LAN.

Before discussing specific Ethernet technologies, we need to discuss

repeaters,

which are commonly used in LANs as well as in wide-area transport. A repeater

is a physical-layer device that acts on individual bits rather than on

packets. It has two or more interfaces. When a bit, representing a zero

or a one, arrives from one interface, the repeater simply recreates the

bit, boosts its energy strength, and transmits the bit onto all the other

interfaces. Repeaters are commonly used in LANs in order to extend their

geographical range. When used with Ethernet, it is important to keep in

mind that repeaters do not implement carrier sensing or any other part

of CSMA/CD; a repeater repeats an incoming bit on all outgoing interfaces

even if there is signal energy on some of the interfaces.

10Base2 Ethernet

10Base2 is a very popular Ethernet technology. If you look at how your

computer (at work or at school) is connected to the network, it is very

possible you will see a 10Base2 connection. The "10" in 10Base2 stands

for "10 Mbps"; the "2" stands for "200 meters", which is the approximate

maximum distance between any two nodes without repeaters between them.

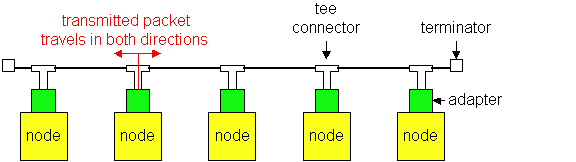

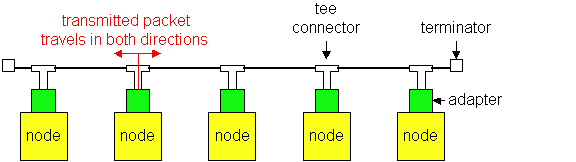

(The actual maximum distance is 185 meters.) A 10Base2 Ethernet is shown

in Figure 5.5-4.

Figure 5.5-4: A 10Base2 Ethernet

We see from Figure 5.4.3 that 10Base2 uses a bus topology; that is,

nodes are connected (through their adapters) in a linear fashion. The physical

medium used to connect the nodes is thin coaxial cable, which is

similar to what is used in cable TV, but with a thinner and lighter cable.

When an adapter transmits a frame, the frame passes through a "tee connector;"

two copies of the frame leave the tee connector, one copy going in one

direction and one copy in the other direction. As the frames travel towards

the terminators, they leave a copy at every node they pass. (More precisely,

as a bit passes in front of a node, part of the energy of the bit leaks

into the adapter.) When the frame finally reaches a terminator, it gets

absorbed by the terminator. Note when an adapter transmits a frame, the

frame is received by every other adapter on the Ethernet. Thus, 10Base2

is indeed a broadcast technology.

Suppose you want to connect a dozen PCs in your office using 10Base2

Ethernet. To do this, you would need to purchase 12 Ethernet cards with

thin Ethernet ports; 12 BNC trees, which are small metalic objects that

attach to the adapters (less than one dollar each); a dozen or so thin

coax segments, 5-20 meters each; and two "terminators," which you put at

the two ends of the bus. The cost of the whole network, including adapters,

is likely to be less than the cost of a single PC! Because 10Base2 is incredibly

inexpensive, it is often referred to as "cheapnet".

Without a repeater, the maximum length of a 10Base2 bus is 185 meters.

If the bus becomes any longer, then signal attenuation can cause the system

to malfunction. Also, without a repeater, the maximum number of nodes is

30, as each node contributes to signal attenuation. Repeaters can be used

to connect 10Base2 segments in a linear fashion, with each segment having

up to 30 nodes and having a length up to 185 meters. Up to four repeaters

can be included in a 10Base2 Ethernet, which creates up to five "segments".

Thus a 10Base2 Ethernet bus can have a total length of 985 meters and support

up to 150 nodes. Note that the CSMA/CD access protocol is completely oblivious

to the repeaters; if any two of 150 nodes transmit at the same time, there

will be a collision. The online reader can learn more 10Base2 by visiting

Spurgeon's 10Base2

page.

10BaseT and 100BaseT

We discuss 10BaseT and100BaseT Ethernet together, as they are

similar technologies. The most important difference between them is that

10BaseT transmits at 10 Mbps and 100BaseT Ethernet transmits at 100 Mbps.

100BaseT is also commonly called "fast Ethernet" and "100 Mbps Ethernet".

10BaseT and 100BaseT are also very popular Ethernet technologies; in fact,

for new installations, 10BaseT and Ethernet are often today the technology

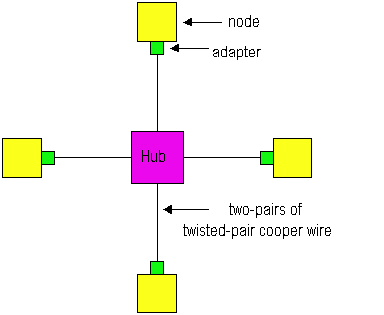

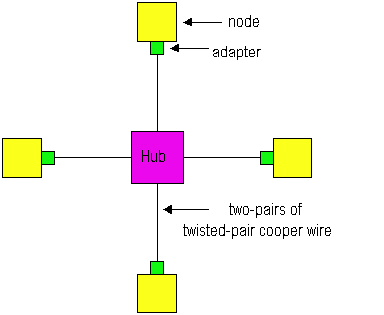

of choice. Both 10BaseT and 100BaseT Ethernet use a star topology,

as shown in Figure 5.5-5.

Figure 5.5-5: Star topology for 10BaseT and 100BaseT

In the star topology there is a central device called a hub (also

sometimes called a concentrator.) Each adapter on each node has a direct,

point-to-point connection to the hub. This connection consists of two pairs

of twisted-pair cooper wire, one for transmitting and the other for receiving.

At each end of the connection there is a connector that resembles the RJ-45

connector used for ordinary telephones. The "T" in 10BaseT and 100BaseT

stands for "twisted pair". For both 10BaseT and 100BaseT, the maximum

length of the connection between an adapter and the hub is 100 meters;

the maximum length between any two nodes is 200 meters. As we will discuss

in the next section, this maximum distance can be increased by using tiers

of hubs, bridges, switches and fiber links. A 10BaseT

In essence, a hub is a repeater: when it receives a bit from an adapter,

it sends the bit to all the other adapters. In this manner, each adapter

can (1) sense the channel to determine if it is idle, and (2) detect a

collision while it is transmitting. But hubs are popular because they also

provide network management features. For example, if an adapter malfunctions

and continually sends Ethernet frames (a so-called "jabbering adapter"),

then in a 10Base2 Ethernet will become totally dysfunctional; none of the

nodes will be able to communicate. But a 10BaseT network will continue

to function, because the hub will detect the problem and internally disconnect

the malfunctioning adapter. With this feature, the network administrator

doesn't have to get out of bed and drive back to work in order to correct

the problem for hackers who work late at night. Also, most hubs can gather

information and report the information to a host that connects directly

to the hub. This monitoring host provides a graphical interface that displays

statistics and graphs, such as bandwidth usage, collision rates, average

frame sizes, etc. Network administrators can use this information to not

only debug and correct problems, but also to plan how the LAN should

evolve in the future.

Many Ethernet adapters today are 10/100 Mbps adapters. This means that

they can be used for both 10BaseT and 100BaseT Ethernets. 100BaseT, which

typically uses category-5 twisted pair (a high-quality twisted pair with

a lot of twists). Unlike the 10Base2 and 10BaseT, 100BaseT does not use

Manchester encoding, but instead a more efficient encoding called 4B5B:

every group of five clock periods is used to send 4 bits in order to provide

enough transitions to allow clock synchronization.

The online reader can learn more about 10BaseT and 100BaseT by visiting

Spurgeon's

10BaseT page and Spurgeon's

100BaseTX page. The reader is also encouraged to read the following

articles from Data Communications on

100Mbps Ethernet:

We briefly mention at this point that both 10 Mbps and 100 Mbps Ethernet

technologies can employ fiber links. A fiber link is often used to interconnect

to hubs that are in different buildings on the same campus. Fiber is expensive

because of cost of the cost of its connectors, but it has excellent noise

immunity. The IEEE 802 standards permit a LAN to have a larger geographically

reach when fiber is used to connect backbone nodes.

Gigabit Ethernet

Gigabit Ethernet is an extension to the highly successful 10 Mbps and

100 Mbps Ethernet standards. Offering a raw data rate of 1000 Mbps, Gigabit

Ethernet maintains full compatibility with the huge installed base of Ethernet

equipment. The standard for Gigabit Ethernet, referred to as IEEE

802.3z, does the following:

-

Uses the standard Ethernet frame format (Figure 5.4.1), and is backward

compatible with 10BaseT and 100BaseT technologies. This allows for easy

integration of Gigabit Ethernet with the existing installed base of Ethernet

equipment.

-

Allows for point-to-point links as well as shared broadcast channels. Point-to-point

links use switches (see Section 5.6) where as broadcast channels use hubs,

as described above for 10BaseT and 100 BaseT. Un Gigabit Ethernet jargon,

hubs are called "buffered distributors".

-

Uses CSMA/CD for shared broadcast channels. In order to have acceptable

efficiency, the maximum distance between nodes must be severely restricted.

-

Allows for full-duplex operation at 1000 Mbps in both directions for point-to-point

channels.

Like 10BaseT and 100BaseT, Gigabit Ethernet has a star topology with a

hub or switch at its center. (Ethernet switches will be discussed in Section

5.6.) Gigabit Ethernet often serves as a backbone for interconnecting multiple

10 Mbps and 100 Mbps Ethernet LANs. Initially operating over optical fiber,

Gigabit Ethernet will be able to use Category 5 UTP cabling.

The Gigabit Ethernet Alliance is an open forum whose purpose is

to promote industry cooperation in the development of Gigabit Ethernet.

Their Web site is rich source of information on Gigabit Ethernet [Alliance

1999]. The Interoperability Lab at the University of New Hampshire

also maintains a nice page on Gigabit Ethernet [Inter

1999].

References

[Lam 1980] S. Lam, A Carrier Sense Multiple

Access Protocol for Local Networks," Computer Networks, Volume

4, pp. 21-32, 1980.

[Bertsekas 1992] D. Bertsekas and

R. Gallager, Data Networks, Second Edition, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs,

New Jersey, 1992.

[Spurgeon 1999] C. Spurgeon, Charles

Spurgeon's Ethernet Web Site, http://wwwhost.ots.utexas.edu/ethernet/

[Alliance 1999] Gigabit Ethernet Alliance,

http://www.gigabit-ethernet.org/

[Inter 1999] Interoperability Lab Gigabit

Ethernet Page, http://www.iol.unh.edu/training/ge.html

Copyright 1996-1999 James F. Kurose

and Keith W. Ross. All Rights reserved.